Water striders illustrate evolutionary processes

How do new species arise and diversify in nature? Natural selection offers an explanation, but the genetic and environmental conditions behind this mechanism are still poorly understood. A team led by Abderrahman Khila—CNRS Senior Researcher at the Institute of Functional Genomics of Lyon (CNRS / ENS de Lyon / Claude Bernard Lyon 1 University), or IGFL—has just figured out how water striders (family Veliidae) of the genus Rhagovelia developed fan-like structures at the tips of their legs. These structures allow them to move upstream against the current, a feat beyond the abilities of other water striders that don't have fans. The researchers identified two genes, hitherto unknown, that are responsible for the formation of Rhagovelia leg fans. Their findings are reported in Science (October 20, 2017).

Rhagovelia belong to a group of insects (Gerromorpha) that stand out for their ability to walk on water. Water-repellent hairs covering their legs make this possible. Unlike other Gerromorpha, Rhagovelia are specialized for locomotion on streams with strong currents using fan-like extensions on their second pair of legs that act as swimming fins. As Rhagovelia alone possess these fans, they offer an ideal model for studying how new structures, or morphological innovations, form during the evolutionary process.

The scientists first wanted to know what genetic information programmed the development of the fans. They discovered two previously unknown genes in Rhagovelia that must be expressed for fully formed fans to appear. When these genes are silenced, Rhagovelia form normal legs, but they lack fans. Deeper investigation revealed that one of the two genes is actually of early origin, having been inherited from an ancestral insect. The other gene is new, however: it is only found in Rhagovelia.

The striking similarity between the two genes suggests that a genetic mutation may have given rise to the Rhagovelia-specific gene by duplication of the ancestral one. The researchers also noted that the genes are only expressed in cells at the tips of the middle legs. This means that the evolution of fans involved at least two major genetic events: a duplication of a gene to yield two copies in Rhagovelia; and the expression of these genes in the cells that give rise to the fans. As these feathery extensions are reminiscent of the fans of Japanese geisha, the newer gene has been dubbed geisha; and the ancestral gene, mother-of-geisha.

Khila's team then had to figure out the purpose of these fans and their importance for these particular water striders. Surprisingly, Rhagovelia move rapidly over still water with or without fans. On moving bodies of water, however, normal Rhagovelia (i.e., with fans) quickly and effortlessly run upstream, while fanless Rhagovelia are no match for the current. What's more? Rhagovelia with rudimentary fans do a halfway decent job—better than fanless Rhagovelia, but worse than individuals with fully developed fans.

These findings reveal that some genetic modifications can lead to the emergence of new structures that directly affect organisms' lifestyles and give them access to ecological niches formerly out of their reach.

Rhagovelia walking on water.

Rhagovelia walking on water.

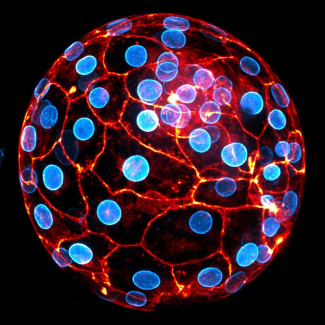

Fan removed from middle leg of Rhagovelia.

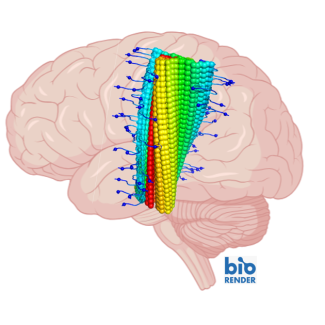

Locomotion habits and niche preference of Rhagovelia and Stridulivelia.

Comparison of fan deployment between untreated and gsha/mogsha RNAi-treated Rhagovelia. Note that despite the reduction of the fan in RNAi-treated individuals, the remnants of the fan are still deployed and retracted just like in normal individuals.

Stream set up showing the condition for the ascension test against current and the performance of untreated compared to gsha/mogsha RNAi-treated individuals.

Taxon-restricted genes at the origin of a novel trait allowing access to a new environment. Santos ME, Le Bouquin A, Crumière AJJ, Khila A. Science, 2017 Oct 20. DOI: 10.1126/science.aan2748 View web site